By Laurel White

One April evening around 7 p.m., Peter Miller got a text from David Edwards, an offensive lineman for the NFL’s Buffalo Bills.

Edwards, who is part of a leadership program coordinated by Miller and former Badger football player and current Miami Dolphins captain Alec Ingold, had a question: Is there any scholarly research about how players mentally frame the pressure they feel during high-stakes games?

“During the AFC championship game, I tried to talk to our guys about pressure,” said Edwards, a former Badger football player, in the text.

But beyond platitudes about pressure creating diamonds or inspiring winners, Edwards wanted evidence-based research to take back to his teammates. His question was rooted in the understanding that high-level players expect strong science not only behind their physical training and rehabilitation, but the psychological aspects of their game.

“There is a space we’re starting to occupy where there’s a void,” says Miller, a professor of educational leadership and policy analysis. “Highly impactful people are eating this work up.”

That work is the charge of Badger Inquiry on Sport (BIOS), a research initiative launched in 2021 through a partnership between UW Athletics and the School of Education. BIOS aims to explore a wide range of complex topics in sports — including leadership, psychology, and societal impact — by harnessing the combined power of UW–Madison’s world-class researchers and its highly regarded Big Ten sports teams.

“One of our goals is to be a bridge between research and athletics,” Miller says. “We want the research we do to draw from the expertise on campus. This will allow us to be better in sports, to coach better, and to innovate better. And, in the spirit of the Wisconsin Idea, we want what we learn to benefit everyone in our state.”

One of the first established strands of BIOS’ research is dedicated to deepening the scientific understanding of good coaching. The researchers’ findings so far have rich lessons for all leaders — on and off the field.

Finding Coaches Who Connect

The main goal of the Wisconsin Coaching Project is to build a better scientific understanding of how coaches and leaders create strong connections between teammates, the kind of connectedness that makes a team better than the sum of its parts.

In the project, BIOS researchers center social capital theory — the idea that individuals and groups can benefit from social networks and connections.

Sara Jimenez Soffa is a clinical professor of educational leadership and policy analysis, director of the School of Education’s Master’s in Sports Leadership program, and a researcher for BIOS who focuses on the Wisconsin Coaching Project. She says centering social capital theory in the project reflects a deeper understanding of how 21st century coaches are approaching their work.

“There’s been a cultural shift in coaching,” Jimenez Soffa says. “It used to be that power and authority was the way you coached — the coaches who would throw chairs — but that isn’t the way anymore.”

To build out a qualitative, evidence-based study, BIOS researchers have tapped into a robust network of successful, community-driven coaches across Wisconsin. One of those coaches is Marques Flowers, the head girls basketball coach at Vel Phillips Memorial High School in Madison.

During an appearance on Miller’s “Sport and the Growing Good” podcast, Flowers said fostering understanding, empathy, and trust between his players as human beings, not just positions on a roster, is vital to the girls’ success on and off the court.

“If you’re doing it right, your kids should be connected to each other,” he said. “Being on a team forces you to connect with people and problem solve and empathize — your success is tied to someone else’s success.”

On Flowers’ team, the girls make space for getting to know what their teammates’ lives are like, including what challenges they may face the moment they step off the 84 feet of hardwood they play on.

“Every kid is going through something,” he said. “And if we’re not aligned as a community around the ideals and values that we all matter, it’s hard to be successful.”

BIOS researchers have also connected with coaches on campus — including some who are legendary figures in their fields.

Landry Levinson, a doctoral student in the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis, recently finished a season shadowing the Badger women’s hockey team and its renowned coaching staff, including the legendary Mark Johnson. Johnson has led the Badgers to eight national championships, the most of any NCAA Division I women’s hockey team. Levinson’s experience will inform his dissertation on how coaches facilitate social capital toward athlete, institutional, and community development.

He was next to the ice when the team earned its 2025 national championship.

“I’ve been so lucky to be embedded with this team,” Levinson says. “There’s a track record of Coach Johnson creating successful players and successful people outside of hockey. His contributions go beyond the players and the team — he has helped grow the sport of women’s ice hockey and facilitated civic engagement around the team. That was really important for me.”

Levinson says one moment in the national championship game crystallized the impact of Johnson’s leadership: When it came down to a make-or-break penalty shot to send the game into overtime, Johnson stepped back. Levinson says Johnson and his coaching staff had spent months building the emotional scaffolding for that moment. They created space for their players to coalesce around leaders within the team by fostering mentorship, facilitating group experiences outside the game, and giving players space to be their authentic selves.

“That’s how it comes down to the last play of the game,” Levinson recalls. “Johnson asked, ‘Who wants it?’ and the players trusted her, they knew she wanted it.”

The players had raised their gloved hands and pointed as one to forward Kirsten Simms. She took the shot, and she made it.

“Their leadership helped foster strong, trusting relationships within the team,” Levinson says. “That supported their decision-making when they needed it the most.”

Other connections between BIOS and coaches across campus range from veteran coaches like Johnson to assistant coaches near the beginning of their careers. A number of current and former UW coaches, including Bo Ryan, Paul Chryst, Greg Gard, and Kelly Sheffield, have appeared on Miller’s podcast. Chris McIntosh, UW–Madison athletic director and alumnus of the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis, is also a champion of BIOS and a key figure behind its success.

As BIOS learns from Badger coaches and passes those findings along, the coaches also have the opportunity to pose research questions to BIOS. Neil Jones, head coach of the men’s soccer team, says he appreciates having an open line of communication with such knowledgeable, hard-working researchers.

“Even the ability to bounce ideas off of them is an opportunity that we cherish, and are thankful for,” he says.

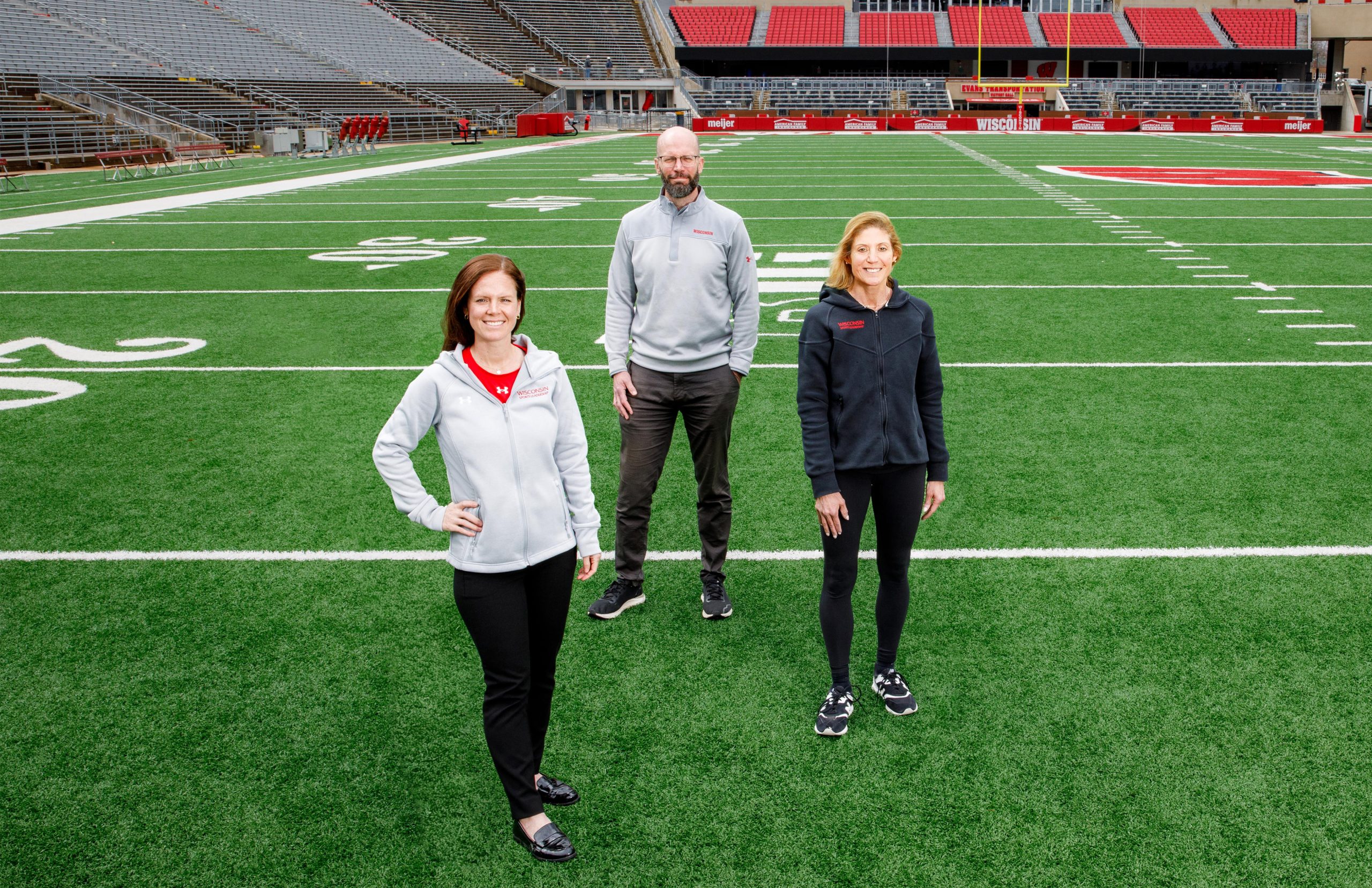

Maria Dehnert, associate director of BIOS, says BIOS is in touch with coaches across campus “all the time.”

“The great thing is that our coaches are at the top of their class,” she says. “They’re so smart, they’re so inquisitive. They don’t have time to do the research, but they have the questions.”

Those questions have ranged from how to interact during a time out to how to run an efficient, effective huddle.

The Wisconsin Coaching Project continues. Initial research resulted in a 2023 report that found coaches created connectedness in five main ways: by bringing their authentic selves to their coaching role, creating shared experiences for the team, being adaptable, using tools like social media to connect outside the game, and using big moments to establish and reinforce connections. The results of that study have been shared in workshops across the state, as well as at the BIOS annual symposium on campus.

“If we can use evidence-based practices to come up with a list of actions that lead to high-quality coaching, and we can take that to athletic directors and coaches across the state of Wisconsin, then we have realized a major part of our mission,” Jimenez Soffa says.

Learning From the Greats

Another way BIOS builds upon and shares its work is through the School of Education’s Master’s in Sports Leadership program, which was launched alongside BIOS in 2021. Students in the master’s program can contribute to BIOS research as part of the program’s field placement, and BIOS’ evidence-based scholarly research is woven into the fabric of the academic program.

Students and scholars in the master’s program also have the opportunity to study sports leadership through the experiences of exemplary sports leaders in Wisconsin and beyond, from College Football Hall of Fame Coach and former UW–Madison Athletic Director Barry Alvarez, who helped shape the program from its infancy, to NBA Hall of Fame Coach Phil Jackson, who has co-taught one of the program’s courses since 2023.

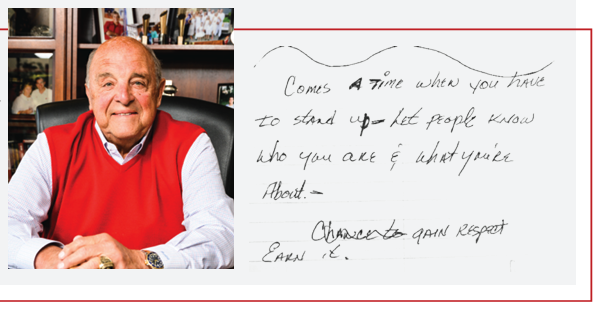

In 2019, Miller asked Alvarez what he thought should be in the curriculum for an academic program focused on sports leadership. Alvarez responded by getting up from his desk in Camp Randall, dropping to his hands and knees, and pulling open the bottom drawer of a filing cabinet. “He said, ‘You should look at my journals,’” recalls Miller. “He starts pulling out these notebooks and handing them to me, one for every year he coached.”

Miller kept and studied Alvarez’s journals for two months. During that time, he was struck by the spirit of openness and vulnerability Alvarez brought to his professional reflections.

“It was kind of cool to see someone who’s got a statue made in their honor struggling with stuff, writing things like, ‘We had a tough loss, sometimes I feel like I don’t know what I’m doing,’” he says. “You could see the highs and lows in real time, in his handwriting. It was just awesome for him to share that.”

Miller says Alvarez’s journals helped him shape a curriculum for the Master’s in Sports Leadership program that values vision, reflection, humility, and an understanding that even the greats sometimes have to push through uncertainty. Alvarez has continued to support BIOS and the master’s program by appearing at a BIOS annual research symposium, joining Miller’s podcast several times, and offering insights to sports leadership classes via Zoom.

Another giant in the field of coaching, Phil Jackson joined the master’s program’s efforts in 2023. Jackson has taught a coaching course alongside Miller every week since. The two, initially connected through basketball coaching circles and sporadic emails, have found a unifying purpose in growing high-quality scholarship and teaching about what it looks like to be an effective leader.

“He has become a real light for me in terms of my understanding of leadership and coaching,” Miller says of Jackson. “To be able to balance practical insight from perhaps the greatest coach ever with our research is our aim.”

Jackson, whose 11 championships as a head coach is the most in NBA history, is considered by the BIOS and Master’s in Sports Leadership teams as a gem in the crown of the programs.

“He’s a deeply thoughtful, intelligent person, and his take on coaching and leadership has transformed sports,” Miller says. “He was one of the first people to bring attention to the mental side of the game into the mainstream of coaching, and he has been a true trailblazer in sport. For our students to be able to interact with him on a weekly basis is unreal.”

The Long Game

For Dehnert, the measure of longterm success for BIOS will be its ability to continue reaching fields of play across Wisconsin.

“In general, we want to positively impact coaches and leaders in sport — and not just college, but in youth sports,” she says. “All of the kids who are going to be playing in 10 years, our hope is that their experiences are better because of the work we did.”

Miller often gets reports outlining the number of Wisconsin kids who play sports — a recent report said there are roughly 180,000 high school athletes in the state — and he keeps them in mind as he works to support their current and future leaders.

“Sport will be a signature experience for many of those kids,” Miller says. “For a lot of kids, sports are the space where they find the most meaning, where they make the deepest relationships, where they feel most open to learning from an adult.”

As a kid and through college, Miller played basketball. Dehnert played soccer. Jimenez Soffa swam. For each of the three, there was a coach who lived in a season of their life but has been omnipresent in all of the seasons that have followed.

“Of course, I love sports for the fun, but I also see sports as a huge space of impact,” Miller says. “Coaches are mentors, teachers, and leaders who have longitudinal relationships with their team members. Supporting their work is one of the richest areas of growth we have for the future of our society. As more universities, schools, communities, and families come together around sports, our attention to coaching should be purposeful. We can help create positive leaders who grow the good in our world through sports.”