By Kari Dickinson

UW–Madison alumnus Brian Raffel’s path to the top of the video game industry has been anything but conventional. A former art student turned high school art teacher, Raffel co-founded Raven Software with his brother, Steve, in 1990, when they got a publishing deal for their first computer game, Black Crypt. What began as a creative side hustle is now a global company — part of Activision/ Microsoft — behind blockbuster titles, including many in the Call of Duty universe.

Through it all, Raffel has remained deeply committed to his Wisconsin roots and steadfast in his belief in the power of education — values that recently inspired a major donation to his alma mater.

“What I learned from the professors and teachers (at UW) — everything I took from that degree — had an impact,” he says. “So I feel like if someone becomes successful, they should try to give back, and stay part of that ecosystem.”

This year, Raven Software gifted 200 computers — valued at $1.26 million — to UW–Madison, enhancing research and learning opportunities for students across multiple disciplines. The computers are being distributed between the School of Education and the School of Computer, Data, and Information Sciences. In the School of Education, they will support courses in the Art Department and the Game Design Certificate program in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction, benefiting hundreds of students annually.

The impact goes beyond teaching, however. In computer science, the machines are being used to support advanced computing and research simulations. “It’s a direct benefit to both education and research,” says John Garnetti, UW–Madison’s managing director of business engagement.

Garnetti was a core member of the team that helped coordinate the partnership with Raffel and his company. By aligning Raven Software’s regular technology refresh cycle with UW–Madison’s needs, the company was able to put high-quality computers — which might otherwise have been discarded — directly into the hands of students and researchers.

“Partnerships like this can come in many forms,” Garnetti says. “It’s not always about writing a check — it’s about creativity and collaboration.”

Garnetti lauded Raffel as “the champion who made it real.”

“He’s someone who truly cares about this community and this university,” Garnetti says.

Where it all began

Raffel was raised in Verona, Wisconsin, as one of eight siblings. His father, a graduate of UW’s College of Agricultural and Life Sciences, worked for the state of Wisconsin as a food supply supervisor. His job took him to farms across the region, where he inspected practices around pasteurization, cheese production, and overall food safety.

“He was very proud of his UW–Madison degree, and so that was just drilled into me,” Raffel recalls.

That pride in education carried through the entire family. One sister, Sandy, earned a master’s degree in bacteriology and conducted Lyme disease research with the National Institutes of Health in Montana. His brother Dave completed a doctorate in medical physics at UW–Madison and is now a professor and researcher at the University of Michigan, with multiple patents to his name.

With such accomplished siblings, the drive to pursue a UW degree was strong.

“I was always competitive, especially with my brother Dave,” says Raffel. “I wanted to get my degree from Madison, and so I went.”

But Raffel’s interests leaned toward the artistic — like his brother, Steve, who would later become his business partner.

“Steve and I were the artists of the family,” he says. “My dad worried, I think, because everything I drew seemed haunted — skulls, ghosts, demons, the whole gallery of the underworld.”

Raffel began his studies at Madison Area Technical College, earning a degree in commercial art. After a stint working in the field, he returned to school at UW–Stevens Point, then transferred to Madison after a semester to complete his art education degree. He earned his bachelor’s degree from the Art Department in 1986.

Raffel went on to teach art at Middleton High School, where he helped develop the school’s computer animation curriculum and coached cross country and track for seven years.

“When I walked into that art room for the first time — after summer orientation with all the new teachers — it was like, wow. I’m responsible for all of this now. This was the real deal — my show,” he recalls.

The birth of Raven

Brian Raffel had just started his master’s degree when he and Steve Raffel joined forces to create Raven Software.

“It really came out of our D&D (Dungeons and Dragons) roots,” says Raffel.

Beyond their artistic talent, Brian and Steve Raffel shared a passion for the fantasy role playing game.

“We loved Dungeons and Dragons,” he recalls. “It was just mind-blowing, because we were both very creative. I remember that first reading of the first game, and I’m like, you mean I can do anything in this world, and I just have to use my imagination?”

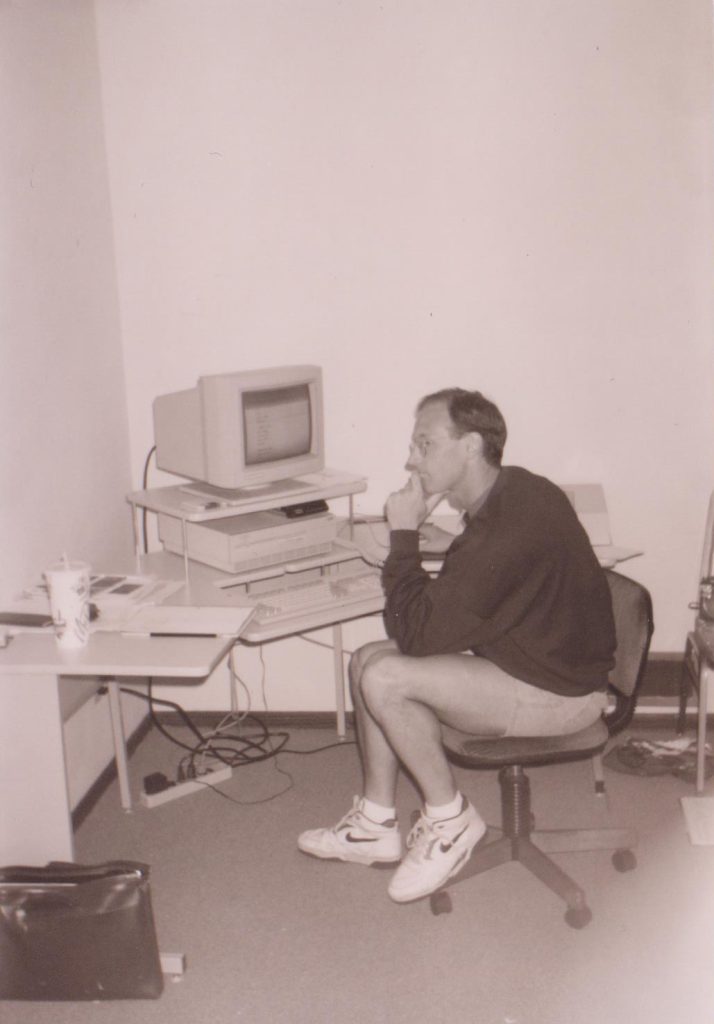

In 1985, the Amiga computer — an early personal computer — hit the market, and the brothers started teaching themselves digital art. One day, while working on a D&D module, they had an idea: Why not create a computer game instead? This spark led to Black Crypt, a role-playing video game where a party of four heroes ventures into a labyrinth to defeat an evil cleric.

With programming help from a friend, the brothers created a demo and sent it to publishers, expecting a long wait for a reply. But within a week, “the phone was ringing off the hook,” Raffel says.

Black Crypt was released by Electronic Arts in 1992 — and thus, Raven Software was born.

Today, the company that started on a single Amiga computer has grown into a global video game studio employing hundreds of people. Over the years, Raven Software has earned a reputation for both original titles and high-profile collaborations, including titles set in the Marvel and Star Wars universes. The company was acquired by Activision in 1997, and Brian Raffel became studio head. Since 2010, Raven has focused primarily on developing titles within the Call of Duty franchise.

Game-changing gift

Even as Raven Software has grown into a global powerhouse, Raffel continues to give back to Wisconsin and the university that shaped him. He sees the company’s donation of computer equipment as a “win-win” — an investment in Wisconsin’s next generation of creators. Fifty new computers are significantly increasing the Art Department’s lab capacity and allowing for an expansion of course offerings. Meanwhile, the Game Design Certificate program in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction is using a dozen new systems to replace aging equipment, ensuring students have access to modern, high-performance technology.

Peter McDonald, an assistant professor in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction, has already seen a big improvement in his game design courses.

“They make a huge difference,” McDonald says of the new computers. “The technology changes so quickly that it is hard to keep our equipment up to date.”

“The tools it takes to build new games are really intensive, and these computers allow our students not to rely on their personal laptops, which aren’t built for the work we’re doing,” McDonald says. “Now, they can use top-of-the-line game development tools.”

In the Art Department, the equipment is opening new creative frontiers.

“I’m very thankful for this gift and what it enables for our students,” says Leslie Smith III, professor and chair of the department. “It builds on the steps we took years ago to incorporate 3D modeling and animation into our curriculum, helping us sustain that momentum and creating experiences that open new, sometimes unexpected creative paths for our students to explore.”

For Raffel, that’s exactly the goal: to give Wisconsin students the resources to dream big — and reasons to stay.

“We’re helping train people in Wisconsin and keep them in Wisconsin,” he says. “I mean, we’ve got the university, a good cost of living, good schools — we’ve got a lot to offer in this state.”

It’s a mission that mirrors his own journey — that with the right tools, support, and imagination, today’s students can become tomorrow’s game changers.