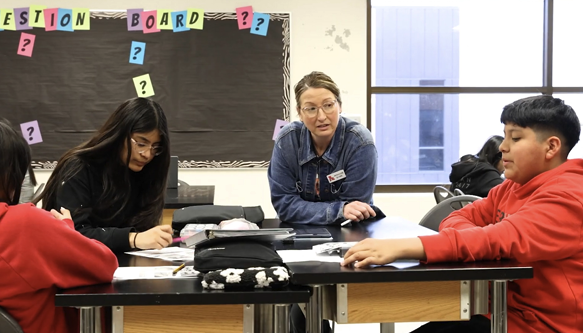

What does curiosity sound and look like in a sixth-grade classroom?

In rural western Wisconsin, students buzz with energy and engage in deep conversation as science teacher Ally LaFave slowly makes her way around the room. Students are broken into small groups of three or four and are sitting at tables with pencils in hand, worksheets to fill out, and colorful binders scattered about.

Like a quiet conductor, LaFave stops in at each of the small groups and nudges her students — and their conversation — forward.

The topic? How to engineer a tsunami detection system — one that can withstand the harsh elements of the ocean and is reliable and cost-effective.

At first glance it looks like a typical, well-run classroom discussion. But there’s something different here.

To the side of each table is a recording device — part microphone, part research tool — observing. The technology is a key component of a cutting-edge artificial intelligence (AI) project led by UW–Madison’s Shamya Karumbaiah that aims to support teachers by analyzing and providing feedback on small-group discussions in real time.

In this room, AI isn’t replacing the teacher. It’s giving her superpowers.

“No AI tool is ever going to replace a teacher,” says Carmen Lee, the director of curriculum, instruction, and assessment for the Arcadia Schools, located about 170 miles northwest of Madison. “The human element is vital and so important on a daily basis. But this AI tool is next level. It’s like having multiple teachers in the classroom at once. I’m blown away by its potential to support our teachers — and, ultimately, student learning.”

Research shows that classroom discussion is vital to student learning. It’s sometimes called the “book club concept.” When people talk about topics as a group, they learn with and from each other — leading to a deeper understanding of the material compared to when a teacher simply lectures at the front of the class.

“Even the best teacher can’t be at every table at the same time,” says LaFave, who has been with Arcadia Schools for 25 years. “This tool lets me see who’s talking about what, and whether they’re understanding the key concepts. I can jump in where I’m needed or help guide a group back on track.”

Developed through a research partnership between the UW–Madison School of Education and the School District of Arcadia, the AI technology both transcribes and summarizes student conversations across multiple tables — and does so in multiple languages, including English and Spanish. It gives teachers a live dashboard on an iPad featuring a summary of which groups are discussing key concepts and having quality conversations, who might be struggling, and whether all students are learning and participating.

The goal is not to judge students or teachers. Instead, it’s to give teachers the insights they need to better engage with students in real time to amplify what’s already working — or to step in and guide those who are falling behind.

“I never imagined something like this would be possible,” says Lee. “I’m not super well-versed in all the AI tools that are out there today. But having access to this tool and working with UW–Madison has been amazing. Being in a rural school, sometimes we’re not exposed to these new things or we don’t get access to them as quickly. So we have really enjoyed this opportunity to be a part of this process and to bring new and innovative resources to our schools that help our students.”

The Importance of Human-Centered AI

Although Karumbaiah has spent more than a decade focusing her AI efforts on impact in education, her early career was centered in the computer sciences. After earning an undergraduate degree from the Sri Jayachamarajendra College of Engineering in India, she worked as a software engineer at Cisco, the digital communications technology company based in California’s Silicon Valley.

She then received a master’s degree in computer science from the University of Massachusetts Amherst, with an emphasis in machine learning. Before arriving at UW–Madison in the fall of 2023, Karumbaiah earned a doctoral degree from the University of Pennsylvania and was a postdoctoral fellow at Carnegie Mellon University in the Human-Computer Interaction Institute.

When asked about the transition to UW–Madison and landing with the nation’s No. 1-ranked Department of Educational Psychology, Karumbaiah says the move into education was an “obvious” choice for her.

“I’ve volunteered at schools and always been very interested in education,” she says. “It’s a good intersection of an area I am passionate about with what I am good at in terms of my computer science and AI backgrounds.”

Today, she leads The Responsible AI for Learning (TRAIL) Lab, which explores where AI fits in classrooms — or if it should. Its efforts are centered on conducting interdisciplinary research in learning sciences, learning analytics, AI, and human-centered design to develop scientific understanding on responsible use of AI for teaching and learning in real-world contexts.

Karumbaiah stresses that her work focuses on human-centered AI for teaching and learning.

“I’ve come to realize that for this work to have the greatest impact on students, we first need to understand what makes good teaching and what’s already working in the classroom,” she says. “What are the human practices and human-to-human interactions that lead to quality teaching and learning in the classroom? We learn this from our partners in Arcadia and elsewhere.”

This is part of a broader vision Karumbaiah and her team have. They are dedicated to co-designing AI tools with educators, students, and communities — not for them.

“We’re not building something in a lab and dropping it into a school,” says Karumbaiah. “We’re talking to teachers and listening to administrators. We’re understanding what they need and what already works — and then we build with them. They are a big part of this.”

The TRAIL Lab is made up of interdisciplinary graduate and undergraduate students from education, computer science, and information science programs.

“This work is deeply collaborative,” Karumbaiah adds. “We need people who understand learning, people who understand technology and coding, and people who understand kids.”

Karumbaiah and her students have visited the Arcadia classroom multiple times over the past 18 months. They have been collecting data, tweaking models, and improving how the AI responds to student speech — especially that of middle schoolers and multilingual learners, whose informal language and mix of English and Spanish often trip up commercial AI systems.

Recognizing ideas expressed in non-dominant ways is challenging. Many AI systems are trained on adult speech, but middle schoolers — well, they talk differently. The project is now working to adapt open-source multilingual models like Llama3 and Aya to “translanguage,” or understand students switching between English and Spanish.

“As school districts across the country struggle with teaching students in a multitude of languages, it’s important to remember the value of bringing students’ home language into their classrooms,” says Karumbaiah. “A very promising opportunity for AI is to bridge the gap between the language the teacher speaks and the different languages that the students in the classroom speak.”

LaFave agrees.

“Our students bring their full selves into these discussions,” she says. “That includes their language, their culture, their way of expressing ideas. If we want them to feel seen and valued, our tools need to understand them as they are.”

Another unique challenge when working with children is making sure privacy and AI safety issues are top of mind.

Rather than sending sensitive data to outside servers, Karumbaiah’s team uses local models — keeping everything on school- or university-owned servers to protect student privacy. While these models aren’t as powerful as proprietary tools, the tradeoff is intentional.

“It’s a balance between performance and privacy,” Karumbaiah says. “But for us, student safety comes first.”

From Research to Real Impact

This research project is housed in the Wisconsin Center for Education Research and funded by the Spencer Foundation until 2027. It also receives support from UW–Madison’s American Family Funding Initiative and Institute for Diversity Science, among others. This project also builds on past connections with the Arcadia Schools and is co-led by Mariana Castro, co-director of UW–Madison’s Multilingual Learning Research Center, and Diego Román, an associate professor with the Department of Curriculum and Instruction.

The classroom in Arcadia is just one site in a multi-year study, but the potential is clear. In addition to supporting teachers, over time the tool could also evolve to support students directly — offering them prompts to refocus when they drift off topic or helping them reflect on how they contribute to group discussions.

LaFave’s students, meanwhile, are already fascinated by the technology. “They ask if they’ll get to see the tool in action,” she says. “It’s one of the first times they’ve seen AI used in school — and not for cheating or shortcuts, but to help them learn better.”

And as rural districts across Wisconsin — and the country — continue to adapt to changing demographics, innovations like this one may be key to ensuring that all students are seen, heard, and supported.

“Education doesn’t need more automation,” Karumbaiah says. “It needs augmentation. It needs tools that amplify teachers’ strengths, respect students’ voices, and help everyone in the classroom do what they already do — only better.”

Related: New UW–Madison fellowship helps teachers examine classroom use of artificial intelligence